Guillaume Poussou

Alice, de l’autre côté du miroir

Photos and audio-visual installations sparked by Lewis Carroll's book "Through the Looking-Glass, and what Alice found there".

Curator: Pep Salvador

November 6th until December 5th 2021

Vernissage November 5th 18:00

At 18:30h and at 20:00h Performance: "Time Machine"

(collective) INVISIBLE TRAVELS AGENCY

Photography: Guillaume Poussou

Production and montage: IfYouMakeMe productions

Time Machine pilot: Tigran Pierre Lee

Curator: Pep Salvador

Texts: Ivan Pintor Iranzo /Lewis Carroll

Script: Anahit Simonian / Guillaume Poussou

Music Score: Joan Pérez-Villegas.

Video Montage: Juan Carrano

Mapping: Pep Salvador

Multimedia Programming: Albert Coma

Alice, de l’autre côté du miroir

Imaginar es siempre viajar al otro lado, abrir huecos en la percepción cotidiana del mundo. Con los años, a veces la literalidad de las cosas se impone sobre la imaginación, y todo cuanto aparece ante nuestra visión, el dibujo geométrico de las baldosas, una ventana, el desconchado de una pared, parecen ser solamente eso. Sin embargo, la imaginación que, como señalara Gaston Bachelard, es la facultad de cambiar las imágenes primeras, supone siempre una invitación al ensueño: las mayólicas se abren como un laberinto palpitante, a través de la ventana se dibuja la posibilidad de surcar la Vía Láctea rumbo al mítico Planeta Hibou, cuyas sendas Tigrán explora cada noche, y el desconchado de la pared revela la geografía visionaria de un universo remoto en el que Alice, antes de pasar al otro lado del espejo, reconoce las huellas de una civilización ancestral y todavía viva.

Los niños no se dejan poseer por la realidad ni anhelan asentar sus imágenes, sino que entran en una relación dialéctica con lo que les rodea.

Quizá la súbita introspección que a veces asalta a todos los niños, la melancolía que los embarga, es el testimonio de su primera constatación ante la mayor parte de los adultos. No les llama la atención que seamos más altos o fuertes, sino nuestra incapacidad para la imaginación, para entablar una relación dialéctica con el mundo y danzar con él, nuestra impotencia para la magia.

Si se llama a la vida con el nombre justo ella acude escribía Kafka, y esa es la esencia de la magia, que, como la imaginación, no crea sino llama, convoca nombres ocultos.

¿Y es que acaso existe algo que provoque mayor regocijo en los niños que inventar una lengua secreta?

¿Es posible que sin los nombres arcanos del “transductor-proyector de vibraciones” y el “generador de secuencias cimáticas” pueda funcionar la máquina del tiempo de Tigran y Guillaume Poissou, un artista que, como el Principito de Saint-Exupéry, nunca ha perdido la doble visión de la imaginación?

Como modernos avatares de Ulises, Tigran y Guillaume se ponen a los mandos de una nave que no es sólo una invitación al viaje “hasta ese país que se te parece tanto”, como cantaba Baudelaire, sino también un Astrolabio-árbol, un Astrolarbre. Porque, como los árboles, no se puede viajar, ascender y alcanzar nuevos horizontes con las ramas y el follaje si las raíces, los rostros que nos abrieron el mundo por primera vez, no son copiosos y benévolos.

Jugar, como dibujar, es descubrir, ir descubriendo, y sólo en el hallazgo, en las artimañas de la invención es posible convocar la felicidad. Pueden cambiar los personajes, el conejo siempre apresurado, la sonrisa enloquecida del gato de Cheshire, los exabruptos de la Reina de Corazones, pero Alice siempre es la misma. Como Mozart escribiendo a Bullinger, la perpetua búsqueda de nuevos horizontes de Alice nos revela que “vivir bien y vivir feliz son dos cosas distintas, y la segunda sin duda no sucederá sin algo de magia”.

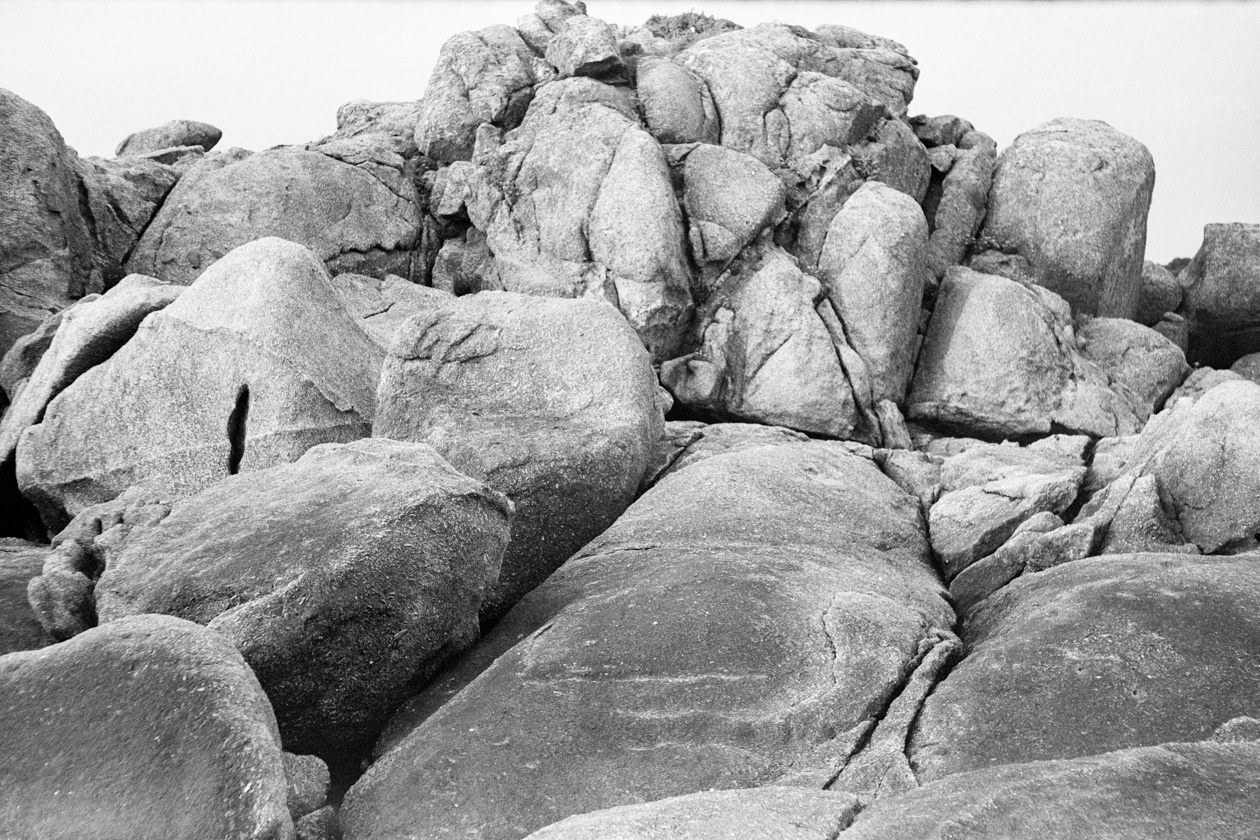

Todas las fábulas modernas nos enseñan a dominar la inclinación a través de las obligaciones, pero hay un espacio de la infancia, antes de que esos cuentos puedan tomar cuerpo, en que el corretear del niño es una perpetua llamada a la felicidad, la invención de nuevo refugio en cada árbol, de un nuevo Edén en cada roca y de una nueva imagen en cada nube. Quizá por eso Alice, como todos los niños, como los adultos cuando necesitamos volver a respirar, experimenta un placer especial en esconderse.

Ivan Pintor Iranzo

Alice, de l’autre côté du miroir

To imagine is always to travel to the other side, to open holes in the everyday perception of the world. Over the years, sometimes the literalism of things imposes itself over the imagination, and everything that appears before our eyes, the geometric pattern of the tiles, a window, the chipping of a wall, they seem to be only that. Nevertheless, the imagination that, as Gaston Bachelard points out, is the faculty of changing the first images, it always supposes an invitation to the reverie: the majolica opens as a throbbing labyrinth, through the window the possibility to cross the Milky Way towards the mythical Planet Hibou gets drawn, whose paths Tigran explores each night, and the wall chipping reveals the visionary geography of a remote universe in which Alice, before she goes to the other side of the mirror, recognizes the traces of an ancestral and still alive civilization.

The kids don’t let themselves be possessed by reality nor crave to settle their images, but to enter in a dialectical relationship with what surrounds them. Maybe the sudden introspection that assaults every kid sometimes, the melancholy that seize them, is the testimony of their first realization before the most part of adults. It doesn’t draw their attention that we are taller or stronger, but our incapacity for imagination, to establish a dialectic relationship with the world and dance with it, our impotency for magic.

If life it’s called with the right name she comes, Kafka wrote, and that is the essence of magic, that, as the imagination, doesn’t create but calls, summons hidden names.

And is there something that causes more joy in children than inventing a secret language?

Is it possible that without the arcane names of the “transducer-vibration projector” and the “climate sequences generator” the time machine of Tigran and Guillaume Poussou, an artist that as the Saint-Exupéry’s Little Prince, has never lost the imagination double vision, could work? And is there something that causes more joy in children than inventing a secret language?

Is it possible that without the arcane names of the “transducer-vibration projector” and the “climate sequences generator” the time machine of Tigran and Guillaume Poussou, an artist that as the Saint-Exupéry’s Little Prince, has never lost the imagination double vision, could work? As modern Ulises avatars, Tigran and Guillaume put themselves at the controls of a ship that it is not only an invitation to the “that country that looks so alike” journey, as Baudelaire sang, but also a Astrolabe-tree, as Astrolabtree (sic Astrolabio-árbol, un Astrolarbre). Because, as the trees, you cannot travel, ascend and reach new horizons with the branches and foliage if the roots, the faces that opened the world to us for the first time, are not copious and benevolent.

To play, like drawing, is to discover, to keep discovering and only in the finding, in the trickery of invention it is possible to summon happiness. The characters may change, the always in a rush rabbit, the frenzied smile of the Cheshire cat, the Queen of Hearts outburst, but Alice is always the same. As Mozart writing to Bullinger, Alice perpetual search of new horizons reveals that “to live good and to live happy are two different things, and the second one will definitely don’t happen without a little bit of magic.” All the modern fables teach us to dominate the proclivity through the obligations, but there is a space in childhood, before those tales can take form, in which the scamper of the child is a continuous call to happiness, the invention of a new shelter in every tree, of a new Eden in every rock and a new image in every cloud. Maybe that’s why Alice, like every child, like the adults when we need to breathe again, experiments a special pleasure in hiding.

Ivan Pintor Iranzo